Ukrainian Architecture and Cultural Identity

Hey ArchiDabblers! We're soon coming to the end of our 2020-2021 blog post series. It's Linda here, and I'm kicking off the countdown of our last three blog posts of the academic year by publishing the cultural context essay that I submitted this semester. Sit back, relax and enjoy reading through my exploration of the role of Ukrainian architecture in creating a sense of cultural identity.

Cultural identity is what binds a specific group of people. They are united by their common practices, traditions and rituals, creating a sense of exclusivity to their community which distinguishes them and sets them apart from other people. In other words, cultural identity is a specific sort of belonging that applies to a select group of people.

The cultural identity of Ukrainian people is an intriguing one. Their past features a plethora of influences on how their identity as a nation has been shaped, and the built environment of Ukraine is no exception when it comes to symbols of their treasured cultural practices and beliefs. Recently, however, the political events that have divided the nation into the east and the west make us, as outsiders of the Ukrainian cultural identity, question what it is that really makes these citizens unique, rather than an indistinctive collation of the remains of all the influences that shape the nation today. Two significant buildings explore this question in identifying how the built environment generates a sense of cultural identity to a population that has been through several generational identity crises.

The Saint-Sophia Cathedral was founded and built in the 11th century following the evangelization of the region of Kyiv in which it was built. This contributed to the spread of Orthodox faith that even influenced Russia centuries later, making Ukraine the country that influenced its neighbouring countries, rather than the other way around. The Saint Sophia Cathedral is an emblem of the introduction of Eastern Orthodoxy to Kievan Rus, chosen by Prince Vladimir The Great because of the ‘aesthetics, art, culture and ritual’ associated with Byzantium, from which certain aspects of Ukrainian cultural identity at the time took influence.

On the other side of the country, the State Industry Building, also known as Derzhprom, was constructed almost a millennium later in 1928 in Kharkiv, a city that was temporarily made the capital city of the Ukraine that was under Soviet rule between 1919 and 1934. The structure is a monumental constructivist work of architecture that lies in Freedom Square, amongst a complex of other equally monolithic concrete buildings that follow the Russian constructivist style that was becoming established during the same period that modernism spread in the western parts of the world.

This essay will explore how three architectural elements - form, materiality and spatial organisation – have been used to generate a sense of cultural identity to the Ukrainian population.

Figure 1 (left): A map to show the total surface area of Kievan Rus that covered parts of Russia, Ukraine and other surrounding countries that today are located in Eastern Europe.

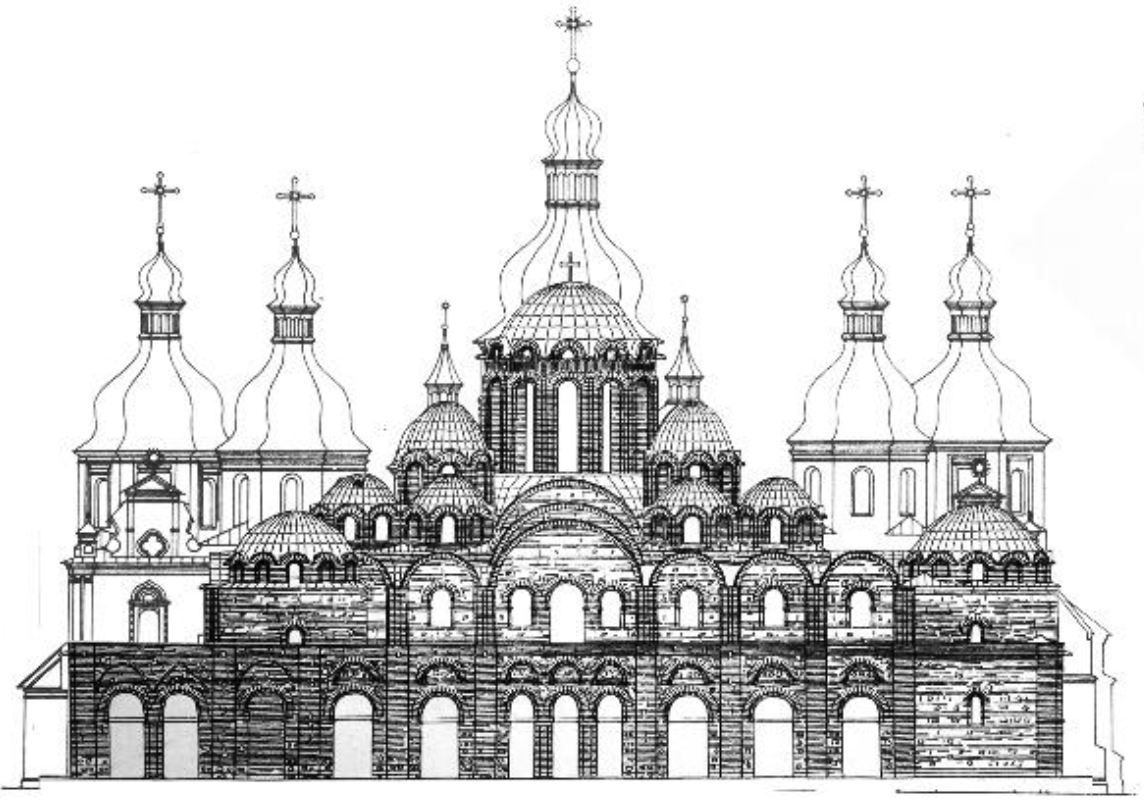

Figure 2 (right): The domes situated on the cathedral convey a sense of hierarchy of the different internal spaces.

Building form generates a sense of cultural identity, as certain geometric forms carry certain meanings which are naturally perceived in a particular way by people who are both involved and uninvolved in the built environment. The Saint Sophia Cathedral is the largest cross-in-square multi-dome structure to be built in history. Its form is just as impressive as its scale, and one of the most notable formal elements of the cathedral are the domes themselves. Ultimately, these have religious connotations: 12 of the 13 domes are a symbol of the presence of Christ’s disciples; the last one represents Jesus Christ himself. On the surface, a brief analysis of the Saint Sophia Cathedral reveals the obvious religious characteristic of Ukrainian cultural identity, relating to the establishment of Eastern Orthodoxy during the 11th century that has remained constant in their national heritage to the present day. This emphasises the resilient nature of Ukrainians; historically, they take pride in making a statement in who they are, and Prince Vladimir the Great did exactly this when trying to establish his rule over Kievan Rus.

A deeper reading of the Saint Sophia Cathedral reveals an alternative view of what the domes show about Ukrainian cultural heritage. According to O. Spengler, the cathedral’s shape itself is seen as ornamental itself. The domes give the building form a quality of elegance, emphasised through their repetition across the structure of the cathedral. In addition, the interior of the Saint Sophia Cathedral is intensely decorated with mosaics and frescos. Ornamentation is a way of manifesting attention to detail and displaying craftsmanship. This represents the Ukrainian people’s talent in their own craft, a shared practice that unites them and thus contributing to a display of their cultural identity through the built environment.

On the other hand, the State Industry Building in Kharkiv starkly contrasts the Saint Sophia cathedral in terms of form. Some may argue that there is nothing elegant about the rigidity of the Derzhprom building – after all, it directly opposes the fluidity of the cathedral’s domes. Smooth curves are replaced with abrupt linear edges, and the flowing forms of the domes are substituted for the uniformity of the planarly identical faces of each façade. This paints an image of the Russian-speaking Ukrainians as complacent to the past rule of the Soviet Union in the 19th century. Inspired by the Russian Constructivist movement of the early 20th century, the submission to the Soviet culture discredits the past historic battles of the Ukrainian people in establishing their own cultural identity against external influences from neighbouring countries.

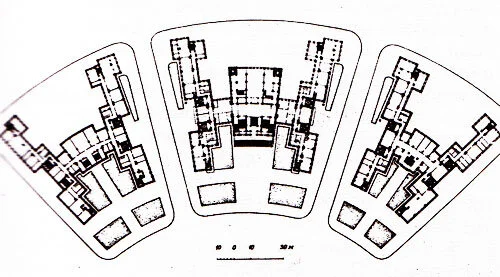

Figure 3 (above): The repetitive, rectangular forms of the State Industry Building in Kharkiv in the Freedom Square have an imposing presence on the wider surrounding context.

However, the rectangular forms can be interpreted as a different kind of elegance. Like the multi-dome element of the cathedral, the State Industry Building features its own formal repetition on a more holistic scale and in a less ornamental manner. Iterations of the same root rectangular mass are replicated across the site, with differences in height, width and depth offering one of the few opportunities for variation in the form of the Derzhprom building. The same could be said for the aspect of Ukrainian cultural identity that the eastern population hold onto so dearly. The State Industry Building can be read as a metaphor of the nations that made up the USSR – geographically, the countries that range from Moldova to Kyrgyzstan, and of course Ukraine, differ in terms of total land occupation, location and shape. Nevertheless, essentially they all formed part of the larger face of the Soviet Union, which existed as a single entity to the rest of the world. It is this acceptance of belonging to a greater good that highlights the unity aspect of Ukrainian cultural identity in the east, which could arguably mirror the same collectiveness that comes with being bound by Orthodoxy.

Formal repetition as a tool of emphasis is common in both case studies, but the subject and consequent cultural identity trait of the Ukrainian people is different across both buildings. Each speaks of a different part of Ukrainian heritage that relates to an aspect of their cultural identity.

Figure 4 (above): The western front elevation of the current cathedral overlaid with an earlier version of the elevation conveys the opus mixtum method in the materiality of the cathedral

The materiality of architecture tells its own story of cultural identity. Since the Saint Sophia cathedral itself had been described as ornamental, decorative features elsewhere were not required to express the ideological nature of the cathedral. Alternating courses of brick and stone in mortar made up the exterior walls of the cathedral. In particular, the opus mixtum method was used. Stone and masonry are some of the most affordable materials in construction, widely used across vernacular architectural precedents. Somehow, this accessible, cheap and common construction method contradicts the image of splendour that one would associate with one of the largest cross-in-square multi-dome structure to be built. For a building that is meant to accommodate the worship of a higher being, masonry seems to be an odd fitting choice of materiality. It suggests that the Ukrainians, presenting themselves to the world as worthy of standing their ground of nationalism, are merely upholding a façade of status portrayed by the ornamental domes and decorative interiors of the Saint Sophia Cathedral, when in reality there is nothing particularly splendid about the structural fabric of the building hidden behind this mask.

The opus mixtum method, however, can also be read from a different perspective. As established, Ukrainian cultural identity, like most national heritages, has historically taken influence from neighbouring countries and beyond. The fusion of stone and brick can be seen as an analogy for this very process of the creation of their heritage. Both materials offer an interesting, unique contrast: and the way that they are combined to form the walls of the Saint Sophia Cathedral is what makes this piece of architecture distinctive. Likewise, it is the exclusive combination of cultural elements that have influenced many parts of the world, rather than the elements of arts and culture themselves, that distinguish Ukrainian culture from the rest of the world that took inspiration from Byzantium or elements of Eastern European countries.

The conversation surrounding Palladianism can be brought into the material analysis of the Derzhprom State Industry building in Kharkiv. Palladianism in the built environment is associated with nationhood; an architectural manifestation of nationalism that binds people together through a cultural art and expresses this consequent national patriotic and prideful feeling of belonging to an exclusive community. Although this discussion often refers to how massive stone structures with pillars and plinths during the sixteenth century era of classical[9] influences on architecture were a way to represent national pride and status, the same can be interpreted in a relatively more modern context. We can identify a shift in the expression of nationalism with the birth of modernism in the global industry of the built environment. During the 19th century, following the Industrial Revolution and the widespread use of concrete in construction, the whole world in one way or another started to produce monolithic, rectangular masses of built structures: office blocks indistinguishable from a residential housing complex. The State Industry Building in Kharkiv is no exception. As the rest of the world quickly becomes acquainted with modernist architecture, the Soviet Union tries to establish its own status and power as a powerful collective entity of nations through its own style that embraces concrete as a new architectural technology. The Derzhprom building is an example of Russian constructivism, in which concrete is the messenger of a nation trying to be recognised, established and distinct from the rest of the world.

Nevertheless, criticisms of the oppressive nature of the Soviet Union in a bid to achieve total conformity across all nations that formed the USSR threaten the argument that Ukrainian architecture binds people by their individuality and how they strive to be established, especially in a globalised world. If we look at architecture as a way to express cultural identity through the lens of individuality and national exclusivity, he monolithic nature of concrete strips away any opportunity that the Ukrainians may have had in order to establish their own identity in the larger federal social state of the Soviet Union. Considering that politically, some eastern Ukrainians to this day identify more with their recently established connections to Russia than to their own geographical homeland, it is difficult to justify a sense of cultural identity that unites the currently divided east and west populations of Ukraine.

Whilst materiality may seem like a controversial architectural element to use in defining the cultural identity of Ukraine, the cathedral and Derzhprom building both demonstrate examples of how these two divided populations still have a common trait between them that is represented through the choice of material used for their building fabrics.

Figure 5 (left): Floor plan of the Derzhprom building in the middle amongst the other buildings in the Freedom Square complex

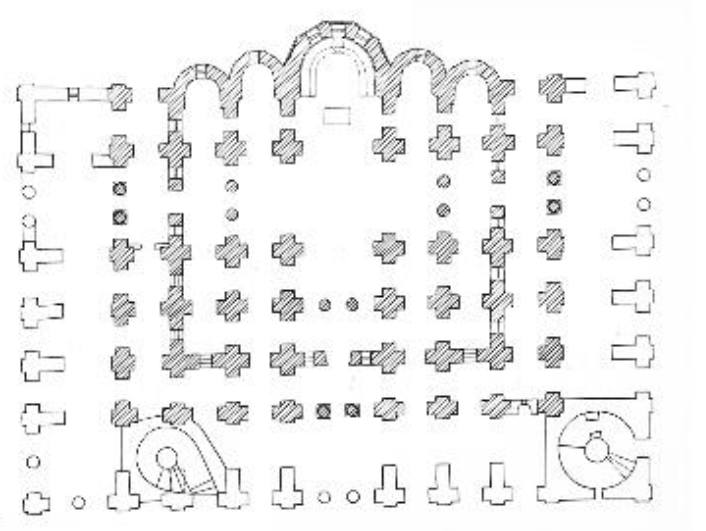

Figure 6 (right): Floor plan of the Saint Sophia Cathedral showing the nave, repetition of vaults and the apses at the end of the sanctuary.

The final argument in relation to how architecture can be used to generate a sense of cultural identity is through the spatial organisation of a building. Spatial organisation can be used as a tool to orchestrate the sequential procession of a building, which in turn can additionally represent aspects of a nation’s heritage and inform common practices and rituals that unite a community.

The Saint Sophia Cathedral features typical spatial features often found in Christian churches. The main nave of the cathedral, as well as the transept, host a series of barrel vaults which eventually open up to the chancel. At the east-most end of the church, five overlapping hemispherical apses echo the words of the priest back to the locals who gather in the sanctuary to worship. The delay in the journey through the nave to the central gathering space of the cathedral offers a chance for people entering the cathedral to transition from seeing themselves as individual beings in the world, to part of an exclusive, collective community of people who share the common practice of Orthodox rituals. It is the single, undivided open spatial quality of the sanctuary that generates a sense of belonging to the distinct cultural identity of the Ukrainian people. This is distinct from the Derzhprom building in Kharkiv – the opportunity for expression of individuality is still present in the ornamentation of the cathedral, whilst the State Industry Building oppresses this with the complete absence of decorative elements altogether.

The sequential procession of the State Industry Building still features an opportunity to generate a sense of belonging to a single group of people who share the same cultural identity. The spatial organisation is more than just an extrusion of the Russian letter ‘Ж’ into a three dimensional structure. Once again, the office floor plan is more or less replicated across the Freedom Square plaza. No matter which volume the occupants inhabit and use, they are always confronted with the same environment, layout and organisation of space. The built environment explicitly unites the occupants as part of the same national entity through the uniformity of the spaces.

Despite political differences between the east and the west divisions of Ukraine, the built environment unites this nation in identifying and representing common traits across the two sides of the country. The western Saint Sophia cathedral in Kyiv and the eastern State Industry Building in Kharkiv may starkly contrast on the surface. However, deeper readings of both structures reveal that the Ukrainian cultural identity is represented in the built environment of both sides of the country. Architecture, through building form, materiality and spatial organisation, generates a sense of cultural identity for Ukrainian people. It is easy to overlook the similarities in what the built environment says about the Ukrainian population, as the turbulent past and political situation clouds any sort of union between the divided population. However, this essay demonstrates that it is only once we understand the story behind each building that a quick physical examination of a built structure cannot reveal, that we begin to identify that no matter which political side a Ukrainian person may favour, they are always connected to their oppositional counterparts by their solidarity, national pride and resilience which has resonated historically throughout the country’s past. Ukraine is not made up of European idealists, or Russian enthusiasts, but a whole community of people who belong to Ukraine in different ways, belonging to two different branches of the same historical and national heritage that forms their common cultural identity.

That brings us to the end of this week's post! Hopefully this post not only enlightened you on some architecture that you might not necessarily be exposed to, but also gave some insight on what kind of work you'll be expected to produce in a second year essay on cultural context.

If you have any questions on essay writing or anything else that we can help with, feel free to get in touch with us through our email at dabbleenquiries@gmail.com. Don't forget to follow us on Instagram too at @archidabble to keep up to date with our content and our Monday Insta posts too.

See you next week!